Capitalism is the only economic system that includes reliable, built-in incentives to solve problems by organically removing bad ideas, products, and companies, and replacing them with better ones in a reasonable time frame, without violence.

Capitalism is not a product with a beginning-middle-end life cycle. It’s an organically evolving system, in a constantly shifting state of change and adaptation. Any part of it – products, services, technology, and people – things that don’t work or don’t deliver value are replaced with things that do.

Late-stage capitalism is a phrase used by people who want to imply that capitalism is doomed to fail, usually with the implication that it will happen soon and that it must be replaced by an alternate economic system (typically socialism, communism or some variant).

In this essay, I’ll share some arguments for why capitalism is the best available system for solving problems and reducing suffering. But let’s start with a little history.

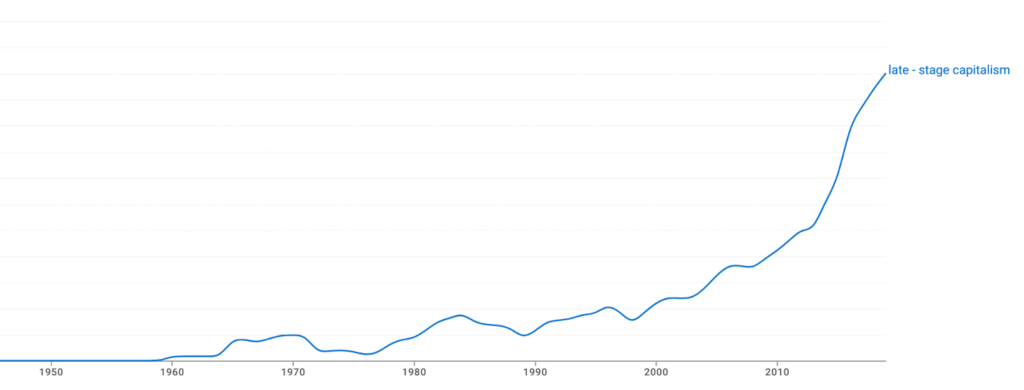

Prevalence of the Phrase Late-Stage Capitalism in Literature, 1945-2019

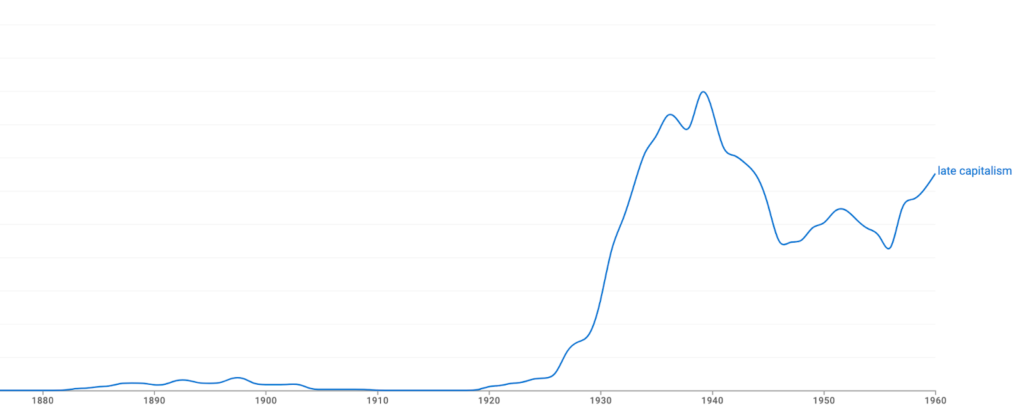

If you haven’t been paying attention, it may seem like this is a relatively new phrase, promoting a new theory. But its roots go back to the 1880s, when Marxist economist Werner Sombart coined the phrase late capitalism, eagerly referring to Karl Marx’s theory that the materialistic excesses of bourgeois capitalism would lead to social revolution.

Late capitalism as a concept must have been irresistible to the budding Marxists, since it implied that the long-promised revolution was right around the corner.

Late-Stage Capitalism Originated as Late Capitalism in Marxist Literature in the 1880s

I’ll be charitable and assume that most contemporary people who use the phrase late-stage capitalism are doing so naively, making a logical leap that capitalism’s problems are equivalent to symptoms of its inevitable decline. Or they are simply denigrating capitalism as a way to signal their supposed intellectualism.

And some do use it to promote alternative systems like socialism, communism, anarchism, or other forms of wealth redistribution. They may be doing this subtly or explicitly, but the message is the same: capitalism isn’t working, and it’s about to fail.

It’s important to talk about our ideas so we can detect errors in our thinking. But the phrase late-stage capitalism is particularly flawed. It begs the question twice, making two false assumptions: First, that capitalism has predefined stages. And second, that we must be in one of the later ones.

The idea of late stage-capitalism also implicitly fails to recognize that rather than being in some “late stage” of capitalism, we are in fact so early with capitalism that we are essentially still at the very beginning. Capitalism can provide a potentially infinite stream of growth that benefits everyone on Earth, and can continue to do so as long as people exist.

Why the Idea of Late-stage Capitalism is Flawed

Late-stage capitalism as a concept has two critical issues:

- The phrase is contains logical flaws which render it meaningless.

- People who use it mistake valid problems with capitalism for critical ones.

The Phrase Late-Stage Capitalism is Logically Flawed

Late-stage capitalism smuggles in two glaring logical fallacies. It implies that capitalism has some known, predefined quantity of stages, and that it’s possible to know which stage we are currently in.

It is always possible to group past events into stages. So it is tempting to think we might do the same looking forward. But this is impossible.

How would we know how many stages to predict? It would be like trying to say how long a poem will be having never heard it before. How would we know if there are “stages” at all?

With capitalism, there is no way of knowing if the present stage is late or early because the future cannot be predicted. People constantly create new knowledge, and unpredictable events happen all the time.

Even when we have a fairly good concept of “stages” in history looking back, a person alive 100,000 years ago would have no way of characterizing their era as the Stone Age, since they would have no way to predict the end of the Stone Age by the forthcoming discoveries of metallurgy, or the invention of copper, bronze, or iron tools. They would not even be aware of the concept of characterizing past eras by the materials used to make tools.

You could also consider the people of the 1960s, who enthusiastically referred to their own time as the Space Age. They were utterly wrong in predicting that space exploration would define their era. Instead, we got the internet, smartphones, and the metaverse. We’ll have to leave advanced space exploration for some future age, which may not even be characterized by space exploration since another more defining characteristic could embody that era.

In the same way, how would people alive today possibly know what stage of capitalism we are in?

It is possible to point out valid problems with capitalism, and theorize how they might lead to capitalism’s downfall. But there is no way of knowing if these problems are characteristic of an early, mid, or late stage. Nor can anyone know if we are about to solve these problems, or if they are relatively minor in comparison to future problems 1000 years from now, which could in principle be many times worse.

Critics of capitalism might guess that we are presently in a late stage, and it’s possible they are correct. But only in the sense that any random guess not prohibited by the laws of physics could be correct.

As it’s commonly used, the phrase late-stage capitalism is also a bad explanation, since the person using it can make infinite variations if their theory turns out to be incorrect. No matter what happens, they can always claim we are actually still in a late stage of capitalism, and that if we wait just a bit longer, they’ll be proven correct. They can always extend the time required, which makes it a meaningless prediction. Moreso, if some unpredictable event were to lead to the end of capitalism, they would certainly take credit for their prediction, even though their prediction was the result of random luck.

For those reasons, anyone who tells you we’re currently experiencing a late stage of capitalism is no better than a sidewalk prophet carrying a cardboard sign, raving about the end of the world.

The Other Error with Late-Stage Capitalism: Valid Problems with Capitalism are not Critical Flaws

Critics of capitalism make another crucial error when they conflate the correct idea that capitalism has legitimate problems with the wrong idea that it is fatally flawed.

Mature people understand that problems are inevitable. In your home, eventually your sink will leak; your air conditioner will go kaput; your driveway will need repaving.

You might tolerate these issues for a while, or you might fix them right away. But none of them are good reasons to predict that your home is about to collapse completely, or that we are experiencing “late-stage housing.” The sensible thing to do is to keep up with the maintenance, or replace faulty items with better ones. Rarely does someone knock their entire house down over maintenance issues.

So we can acknowledge that capitalism currently has the following known problems, without making an illogical leap to assume that capitalism is critically flawed.

Real problems we currently experience in capitalism

- Monopolies and oligopolies (in the short-run)

- Tragedy-of-the-commons (self-interest issues)

- Issues with demand-inelastic goods and services

- Economic and status inequality

- Instability

- Risks of worker exploitation

People may have different opinions about the severity and significance of these problems. Nobody intelligent would deny they exist. But what many miss, is that a capitalistic economy is both the source of these problems and the best solution we have for them.

Capitalism is the only economic system that includes reliable, built-in incentives to solve problems by organically removing bad ideas, products, and companies, and replacing them with better ones in a reasonable time frame, without violence.

Capitalism is not a product with a beginning-middle-end life cycle. It’s an organically evolving system, in a constantly shifting state of change and adaptation. Any part of it – products, services, technology, and people – things that don’t work or don’t deliver value are replaced with things that do.

In this way, capitalism is like representative democracy.

How capitalism is like representative democracy

Both representative democracy and capitalism are antifragile systems with built-in error correction mechanisms. They leverage the power of people to make choices and take action based on their individual preferences, actions which they are accountable for.

All systems have problems, but when mechanisms exist for participants to create solutions, those solutions improve the system for everyone. It is true that those solutions create even more problems, but solving problems is vastly preferable to stewing in them. And all solutions contain new knowledge that prevents worse problems in the future.

Both systems, capitalism and representative democracy, have built-in feedback mechanisms for people to try solutions to problems, then discard the ideas that don’t work relatively quickly. Anything can be improved upon if people are willing to try.

In a democracy, solutions take the form of new political ideas, spread and improved through discourse and debate, and implemented through voting for representatives who enact policy. When representatives put bad policies in place, voters can push for those policies (and sometimes the representatives) to be removed and for new ones to be tried.

In capitalism, solutions take the form of products, services, and employment arrangements created by entrepreneurs and employees that spread and improve through price signals, competition, purchasing, and employment decisions in the labor market.

Companies usually get rapid feedback through reduced sales when ideas or products go wrong. They can then try new approaches or go out of business.

Employees get feedback about the value of their services through the signal of wages, and being hired or fired. They can then learn new skills or try new approaches to work.

Something counterintuitive but crucial to understanding both representative democracy and capitalism is that when they work well, they create more problems. This seems wrong because problems are bad, but when problems are solved, they tend to replace worse problems with not-as-bad problems, and in this way we make progress. When people solve problems, they also increase our shared store of general-purpose knowledge, which in turn creates better ideas, and so on.

More About How Problems Are Solved Under Capitalism

Most arguments for capitalism rightly focus on so-called free-market solutions. These free-market solutions are the source of capitalism’s strength and resilience. When I say “free market,” I don’t mean completely unregulated markets with no recourse, just the most open markets that society can live with, erring on the side of less regulation.

There are also situations where free-market solutions can create situations where everyone is worse off. Under those circumstances, government regulation may solve key problems, provided it is done under a system where it is easy to remove regulations which turn out to create more harm than they solve.

Free-Market Solutions

Problems are solved via the free market by companies and entrepreneurs creating new products and through consumer purchasing signals. If people like a product, they’ll demand more of it and pay a higher price. If they have a problem with a product, they can stop buying it, or buy an alternative. If they wish to influence a company, they can leverage the fact that a company needs money to survive.

Knowing this, people can buy less of a company’s products, or use their right to free speech to voice their concerns publicly about a product or company, dissuading others from purchasing those products. And in extreme cases, they can join a advocacy groups and petition their government to regulate the product.

All of these actions reduce revenue for the company, and it will respond in a way that it believes will allow it to survive. Over time, this process will result in the company solving the problem with the product, finding a new product-market fit, discontinuing that particular product, or going out of business entirely. Critics might highlight how companies have often allowed harmful products to be sold, but they will have a hard time pointing out any example where this has happened over the long run because over time, people will demand change. And under capitalism, they have an avenue to do so.

The same thing applies to conditions for workers. Just as the public can choose between competing products, under capitalism, people can choose between competing workplaces.

Consider what happens when people are dissatisfied with a company under other economic systems like socialism or communism. What is the motive of a state-run company? Is it to export products to sell at a profit for the government? Provide products for citizens? Provide jobs? Sustain a state bureaucracy? Or provide positions of power for local politicians in exchange for political favors? Under capitalism, at least you know the motive of the company: to earn a profit. And you can use this as leverage.

In most state-run economies, citizens have to take the government at their word. They cannot know the honest answers and have no clear way to take action if that company is causing a problem. They have no leverage and are helpless to change the situation.

Regulatory Solutions to Capitalism’s Problems

Sometimes, a problem will cause people to be harmed before the free-market process can correct it. A certain amount of harm is expected in any system. Still, we should take steps to avoid severe or recurring harm, as long as those steps don’t cause too many unintended consequences.

Limited democratic government regulation is an excellent way to handle this. A good example is regulation solving the problem of air pollution in cities. EPA regulations reduced smog and improved air quality. This likely resulted in better health for people living in cities, a tradeoff that you can argue was worth the downside of reducing industrial output.

But we should always err on the side of as little regulation as possible and ensure that any regulation can be repealed if it turns out to be too onerous. Regulation doesn’t just prevent problems, it also creates them by preventing solutions to future concerns. For example, we could now have practically unlimited cheap, clean, carbon-free energy; however, some environmental groups have made it so it’s currently impossible or too expensive to develop nuclear power plants because of their stance against the production of any amount of nuclear waste.

Another free-market problem with a regulatory solution is monopoly/oligopoly. By controlling the market, these situations make it too difficult, if not impossible, for new entries into an industry. New products are not developed, and society loses out. In these cases, regulators might step in to break up an oligopoly or prevent a company from getting monopoly power in the first place. But they should be careful not to create the same problem they are attempting to solve by limiting a large but not-yet monopolistic company’s ability to innovate.

Regulations can also prevent small companies from competing fairly. Large companies who want to add barriers to entry in their industry have lobbied for some of the most burdensome regulations. One such regulatory barrier is the franchise agreements that telecommunications companies often have with local governments. These agreements often grant exclusivity to a single provider in a given area, making it difficult for new competitors to enter the market. Another is healthcare, where only large, established companies have the resources to complete large-scale clinical trials needed to bring new drugs to market.

Companies or customers becoming untrustworthy can be another problem in a free-market system. When buyers or sellers refuse to honor agreements, the cost and risk of doing business increase, and the whole system can break down, making developing new ideas and products less likely. It is, therefore, pragmatic for governments to play a role in enforcing contracts.

We should also touch on the problem of instability created when people feel (rightly or wrongly) that the current economic system has wronged them. In the past, this perception of oppression has led to violence, and even government collapse. Ironically, this has not happened yet with capitalism when paired with representative democracy, possibly because alternative systems have already been tried with little success.

A final free-market problem with capitalism that could benefit from regulation is in cases where certain goods or services have strong inelasticity of demand. For example, consumers purchasing utilities or life-saving prescription drugs will likely pay whatever price if there are no acceptable alternatives. For this reason, you could argue that markets for these goods are not free, and capitalism does not work well in these situations.

However, we should remain open to the idea that free-market capitalism can provide benefits even here. For example, while the United States is known for having costly healthcare, it is also the world’s leading source of medical advances and scientific discoveries, likely because of the substantial financial incentives for developing beneficial new treatments. It’s worth noting that the more affordable healthcare systems in other countries directly benefit from the innovation that comes out of the US system.

What About the Problem of Inequality in Capitalism?

For some, inequality is the most glaring problem with capitalism. Some people think it is morally wrong for some people to have so much while others have so little. It seems unfair.

Others may make instrumentalist arguments. They may point out that high inequality reduces social cohesion because people become suspicious of each other when they perceive unfair outcomes. Or they may wrongly believe that inequality is a sign of malfeasance because wealth accumulation can only happen by taking it from other people. And further still, some might argue that inequality leads to power being held by relatively few wealthy people.

Moralist Arguments About Inequality

Moral arguments against capitalism are based on fairness. For example, someone might believe that housing is a human right or that no one should starve while billionaires exist. These are moral positions worthy of discussion, but it needs to be determined how we might implement the changes suggested by these slogans without causing even worse problems.

It is hard to claim that we should redistribute property, for example, since that may lead to significant violence, and worse outcomes should the beneficiaries of the redistribution fail to contribute to society adequately (which would be unsustainable), or should the property be redistributed unfairly. Large-scale communal property and wealth redistribution systems have been tried without long-term success. Most communist and socialist countries eventually spiral into dictatorships or oligarchies with extreme inequality.

A solution that causes more damage than the problem it’s trying to solve is not a solution. The best way to address the problems of capitalism is to increase our moral and political knowledge. Increased knowledge will reduce suffering and decrease the chance of violence. But without better theories, it would be unwise to take significant action.

Instrumentalist Arguments About Inequality

The instrumentalist arguments are more concrete, such as the idea that financial inequality causes social instability because people compare themselves to others and claim that the differences result from social unfairness. It is unclear whether this is human nature or a persistent antirational meme, but when someone perceives another as having cheated or taken advantage of others to get ahead, they tend to become naturally suspicious.

The problem is, in most cases, those suspicions are unfounded. Most wealthy people earned their money in ways (at least in principle) available to almost anyone.

The case of inheritances is more problematic for people to accept because someone who inherits money is different from the person who created a valuable product or service. In other words, “they didn’t earn it.”

But we should nevertheless accept generational wealth, because telling people how to allocate resources to their own family is morally wrong. So long as people are legally and socially responsible for their family members, they should get the most say in how to care for them. And the effect of inheritances appears to be vastly overstated anyhow. A 2018 study found that only 21% of millionaires inherited any money at all. And another in 2019 found that only 24% received an inheritance.

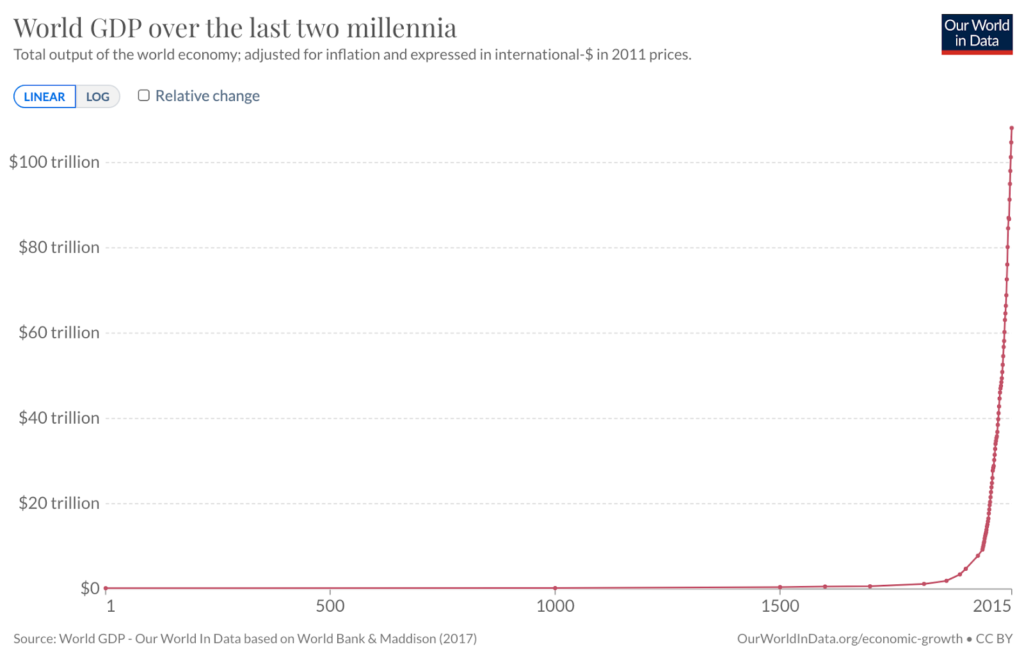

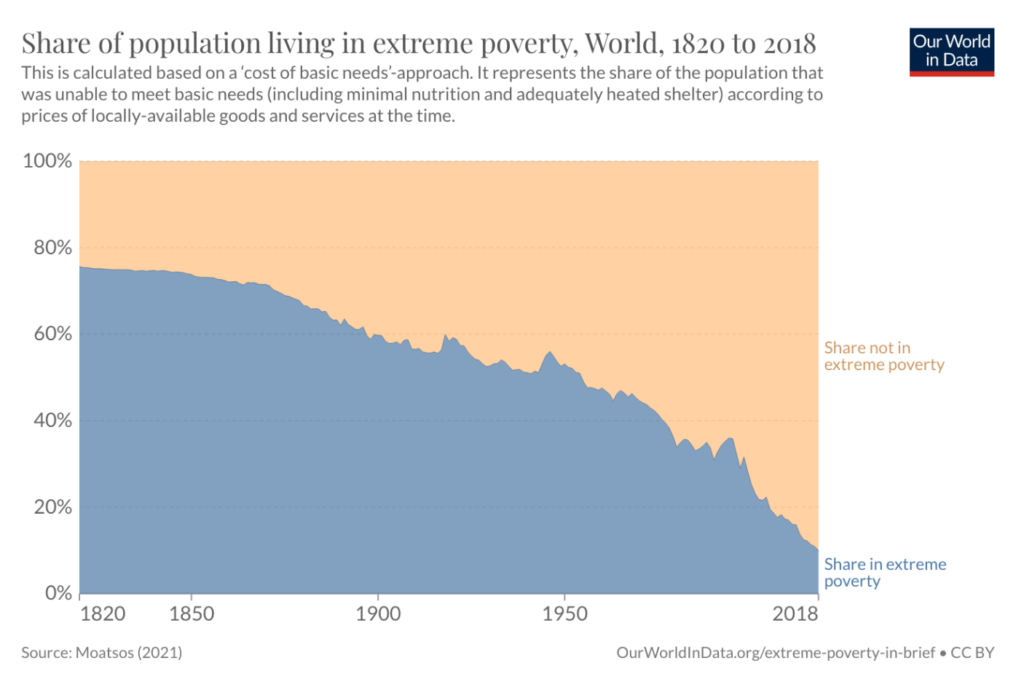

Those who believe wealthy people get their wealth by taking it from someone else do not realize that the world is not a zero-sum game. One person gaining wealth does not mean another person has lost it. Global wealth has increased significantly over time, leading to many escaping poverty.

How could total wealth have grown if wealthy people took their wealth from others? It couldn’t have. Wealth is not ill-gotten by default; it is almost always created by someone bringing a product or service to market that others find valuable enough to pay for.

Another instrumentalist critique of inequality is it concentrates problem-solving ability unfairly among the wealthy. For example, Elon Musk would not have been able to create Tesla and solve the problems of making electric vehicles cool, affordable, and popular or significantly reducing the cost of orbital transport at SpaceX, without first having acquired sufficient wealth through the development and sale of his first company Zip2.

It is reasonable to claim that many more people with highly beneficial product ideas cannot realize their ideas because they lack access to wealth. It would undoubtedly be great if everyone on Earth had the wealth and inclination to tackle big problems like this. Yet, under capitalism, anyone with a good idea and an internet connection can pitch their idea to an investor. If people believe in the idea, it could be funded, even if its profitability is unclear.

Alternate economic systems would require the person’s idea to be approved by a central authority, which would prevent most good ideas from being tried. So while it’s true that under capitalism, the ability to invest is mainly limited to the wealthy, there are opportunities for getting funding for a new idea or product, as opposed to having a limited central authority making all investment decisions.

It Sounds Like You Don’t Care About the Poor

I probably care more about the poor, and humanity in general than most people. This is partially, because I have myself been very poor. After making a few terrible life choices, I spent about two years living in poverty, frequently without enough money to buy food. Only 10% of Americans are in that situation, but I can commiserate with them. Having to steal your groceries so you can eat something before bed is not a situation I would wish on anyone else.

We will face massive problems in the future. These may include a lack of education, disease, and food and energy insecurity. The poor will bear the brunt of these issues, and our goal as a society should be to get as many people out of extreme poverty as possible by continuing the trend of the last 200 years under capitalism.

And while global poverty is rapidly declining, even the wealthiest person today is still extremely poor compared to possible future living standards. 99% of all the kings and queens in history did not have access to a hot shower, much less Amazon Prime. There is no reason we cannot continue to make the same kind of progress in the future.

There are also much bigger problems which could eradicate every poor person on Earth, not to mention every other human. Here I’m thinking of global pandemics, giant meteors, gamma-ray bursts, the rather colonialist and inevitable expansion of the Sun, and so on.

No laws of physics prevent us from solving these problems; if one of them eradicates humanity, it will be our fault for not progressing fast enough. The responsibility for solving these problems and others is ours. These solutions require rapid growth in wealth and knowledge, precisely the kind of rapid growth that is possible under capitalism.

Isn’t This Just Techno-Utopianism?

No. All forms of utopianism are silly because they assume that if we could just fix all the problems, that life would be perfect. But we can never fix all the problems. Problems are inevitable.

However, we can reduce the likelihood that any one problem will cause massive suffering by making sustained technological, social, moral, and political progress.

Nothing prevents humans from improving our understanding of any form of knowledge. Thus, we should commit to systems allowing for rapid experimentation and falsification of our ideas. We will make an infinite stream of mistakes. But we can also create an infinite stream of new knowledge which improves people’s lives.

It’s not a utopia; it’s just our best shot at a future with a positive technological, social, moral, and political outcome.

Why the Idea of Late-Stage Capitalism Is So Attractive

1. People believe they would be happier or more free if they were living under a different system

This might be the most common refrain of anticapitalists. They imagine themselves as able to pursue some full-time creative activity which is currently not possible under capitalism.

Some issues with this type of thinking are:

- It’s a bad explanation for living an unfulfilled life, because no matter someone’s situation, they can always say they would be able to self-actualize if only they had more time, money, etc. The problem is always some outside factor, never themselves.

- Your ideas about your own creative potential and the value of that creativity may be exaggerated.

- It imagines that the replacement system is somehow able to provide more adequate food, shelter, and time for creative pursuits than capitalism. But historically, people living under replacement systems like socialism/communism have had to spend much of their time and energy navigating the idiosyncrasies of a corrupt system, waiting in line for basic necessities, working a job they don’t have any passion for, and living in uninspiring government housing.

2. Capitalism can feel like too much responsibility

Work sucks. I know. It’s nice to imagine a system where you don’t have to work so hard or make so many choices. Constraints are a normal part of life. Capitalism is an environment for people who are comfortable making choices under constraints, like which career to choose, and where to live. Some people might wish to not have to make these choices.

But under capitalism, you can easily choose to coast by while respecting the choice of others who want to embrace the system. Alternative economic systems do not offer this choice, so I suspect most people would choose capitalism if given the option. That is why the boats go from Cuba to Florida. No one risks the journey in the other direction.

3. It explains valid frustrations with capitalism

The concept of late-stage capitalism is attractive because it helps to provide a framework for understanding economic, social, and environmental problems. People feel constrained because they see that they are dependent on others for earning money to pay for things. Identifying capitalism as the root cause of these problems can make it easier for people to understand and articulate their concerns and connect with others who share their views.

4. It prompts people to think about alternative systems

Concern that capitalism is nearing a “late stage” may help people consider improvements, alternatives, and better versions of capitalism.

5. It helps people improve their status (real or imagined)

Using the phrase late-stage capitalism allows the speaker to imply they have special knowledge about the future. While they often have no practical suggestion for a replacement system, they still enjoy a real or imagined social benefit from acting as if they know the next big thing.

6. It helps people feel better by shifting blame and responsibility to external factors

People may use the concept of late-stage capitalism as a way of expressing their frustration or dissatisfaction with their current economic situation. For example, they may attribute their economic struggles to external factors such as corporate greed, systemic inequality, or government policies rather than their own actions or circumstances.

This may be a valid critique in some cases, as external forces can contribute to an individual’s economic inequality and hardship. But under capitalism, the vast majority of individual situations can be self-improved by individual work and creativity. Alternative systems do not allow people to control their situation as readily as capitalism does.

7. It’s a manifestation of envy

While many people who critique capitalism do so from a place of empathy, solidarity, and a desire for a more just and equitable society, others feel a sense of latent envy when they see others operating more successfully than they are under capitalism. Many would feel secure if capitalism were to end and be replaced by a system with enforced equality.

Abandoning Late-Stage Capitalism

Hopefully by this point, you’ve been convinced that the idea of late-stage capitalism is so flawed as to be useless. Besides the logical flaws that come with predicting the future, the error-correcting properties of capitalism, especially in a representative democracy with thoughtful regulation, mean that capitalism is potentially the only system that can deliver the kind of growth needed to solve fundamental problems like poverty, not to mention existential problems which could kill billions, or even wipe out the human species. While it has many legitimate concerns, capitalism can be their source and solution.

I’ll leave you with a story my father-in-law told me about his friend Eugene who grew up in the Soviet Union. My father-in-law had asked Eugene what they were taught about the United States growing up.

Eugene said that they were taught that capitalism was a theory, a model that the US tried and failed. But the catch was their US history ended with pictures of the 1929 crash and the Dust Bowl. Eugene said they never really learned much else, and capitalism was downplayed as a failed model for Soviet students.

He continued by saying that occasionally, people would suggest that they heard that the US was different from what they were being taught. But they had no contact with the outside world because the government protected them (against enemies). He said that this talk was shut down for fear that the government would convict you of promoting propaganda.

I share this as it’s relevant vis-a-vis alternative methods to capitalism. Imagine a model like China, North Korea, Cuba, or the former USSR – the only way it works is if you keep your people from communicating with the outside world, and the only information they get is from the state. It’s hard to fathom, but that is how they live. Think about what the state must do to preserve this model.

If you can only get your food from one restaurant and are not even allowed to know there are other restaurants, the one you have may not seem too bad. Either way, he said, you don’t have a choice.

I run a small SEO consulting business in San Francisco, CA. I like to write a little bit and get in arguments with my friends. It’s the only way I can make sense of the world.